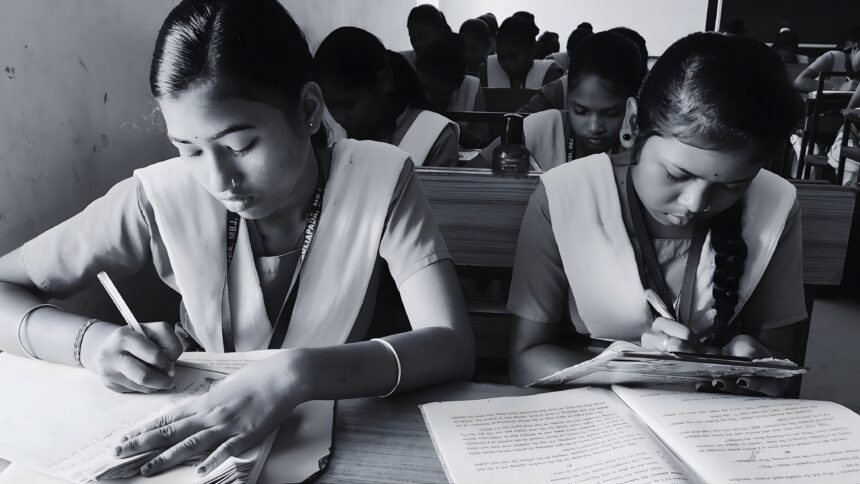

In 2003, students from different parts of rural Odisha came to participate in the Rural Mathematics Talent Search Programme at the Institute of Mathematics and Applications, Bhubaneswar. Just before the program ended, they received an unusual assignment to write their village biographies. As they spent 15 to 20 days gathering memories and stories from their elders, none of them could have imagined that their efforts would one day inspire global initiatives to document village histories.

Two years later, in 2005, noted people’s science activist and eminent journalist Sudhir Pattnaik placed 83 student notebooks in my hands. Each one contained the life story of a village. I expected to find what most would expect from such an exercise—basic details about the village’s past environment, present-day happenings, festivals, food, ornaments, and other cultural aspects, all collected through simple conversations with grandparents.

But the moment I opened those notebooks, I was stunned.

The depth of observation, the nuance of understanding, the careful attention to detail—could this really be the work of children writing about their own villages? It was then that I truly grasped the vast reservoir of imagination within these young minds, and the profound respect and affection they held for their homes.

Let me share just one example—one small instance—of how their writings touched me so deeply.

A Child’s Vision of Inequality

Sohna Parveen, a Class VI student from Khatiguda, Nabarangpur, wrote:

“In our village, Maa Mangala Thakurani resides as our village deity. Because the fame of our goddess has spread across the nearby region, people say that the name of our village, Khatiguda, comes from this very word khyāti (fame). Our village has existed since ancient times. It is impossible to say when it was first established.

Most of the people in our village are Tribals. On the southern side of our village flows the Indravati River. Across this river stands the Indravati Dam Project. This river-dam project is the second largest in the whole of Asia. Around 2,000 people live in our village. As the project area became the headquarters of the block, the population has increased over the years.

Beside our village lies the project colony. The employees of the project live there. People in the project colony generally stay in pucca houses. They are well-educated and employed. Their social standing is quite high. But in Khatiguda village, people still live in houses made of mud and thatch. Their condition is very poor, like darkness beneath a lamp.

Because of the project, roads have improved, a market has developed, and vehicles now pass through the area. But the condition of the Tribals of Khatiguda has not changed at all.

In our village, Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and Tribals live like brothers. We think of ourselves as Indians and work for the progress of our country. But today, those who live in hardship in our village are looked down upon by the newly educated and well-off people, just as one would look at insects. There are no Gandhi or Gopabandhus anymore to serve and care for them. In this fast-moving world, everyone thinks only of themselves.”

In 2003, a Class VI girl presented this analysis—collected from conversations with her village elders—with such clarity and moral force that something shifted within me.

At that time, I had already completed my Master’s in Political Science from Vani Vihar, my Bachelor’s in Law, and my Master’s in Journalism and Mass Communication from IGNOU. Yet all my education felt pale before the understanding and sensitivity of this sixth-grade child.

Her metaphor struck me most: “like darkness beneath a lamp.” Development had arrived at her village’s doorstep, yet those who needed it most remained untouched. She could see what so many adults choose not to—the cruel irony of progress that bypasses the marginalized.

I realized then that we are failing to create an environment that nurtures children’s natural curiosity. Especially during their school years, when their affection and respect for their village is at its peak—if we encourage them to ask questions about their own communities, it could completely transform their thinking and awareness.

An Unexpected Connection

Years later, during the heart surgery of Professor Swadhinaranda Pattnaik Sir, I met one of his former students. He is now an associate professor at an engineering college in Bhubaneswar.

In conversation, I mentioned that I had been working to encourage schoolchildren to write their village biographies. His eyes lit up immediately.

“Ma’am, did you make a video on Khatiguda during the COVID-19 period?” he asked. “During those times, I used to create videos from the ‘Our Village Our Life’ book and train hundreds of students to write their village history and culture while staying at home. We continued this work until 2023.”

I asked him how he knew about Khatiguda.

His answer stopped me in my tracks: “In 2003, more than 80 of us wrote the biography of our village. Sohna Parveen wrote alongside us.”

My heart raced. “Do you still remember what you wrote back then?”

“What are you saying, ma’am?” He smiled. “Writing our village’s biography was such an exciting experience that we have never forgotten it—and we will never forget it. That work inspired us deeply.”

A Movement Takes Root

Only then did I fully understand why children in Paikmal—especially the girls—were showing such incredible enthusiasm for this work, gathering in hundreds to document their villages’ histories. These girls now travel from village to village, recording the life stories of their own communities.

Though the work continued quietly through local initiatives over the years, it gained tremendous momentum during the COVID-19 pandemic when students, confined to their homes, turned to documenting their communities with renewed vigor.

I once believed that such deep affection for one’s village might not exist in areas close to cities. But this year, on April 1st, when Samadhwani announced a village biography writing competition for Odia Language Day, girls from villages around Khordha city participated with tremendous enthusiasm, documenting their own communities with pride.

Taking It to the World Stage

Today, this work has transcended borders, inspiring communities worldwide to reclaim their narratives. In 2025, joy∞untu-a Munich-based platform connecting community-led initiatives globally, helped bring the Village History Initiative to new audiences.

Inspired by our Village History and Food Culture Documentation initiative supported by WASSAN India and the Odisha Shree Anna Abhiyan, joy∞untu recognized how this model beautifully demonstrates what happens when knowledge flows across generations and communities lead their own narratives. Together, we are translating students’ writings and sharing their experiences internationally, expanding the model to communities in Benin, Germany, Guatemala, and El Salvador through participatory grant making, where communities themselves decide how resources are allocated to preserve and document their heritage.

As joy∞untu emphasizes: “Preserving heritage is not just about remembering the past-it’s about shaping the future together.”

This growing international interest set the stage for a significant milestone.

On November 11, 2025, World Millet Day, the Government of Odisha’s Department of Agriculture and Farmers’ Empowerment organized an international conference. The seventh session featured a special FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) panel on “The Role of Women Farmers in the Preservation of Agricultural Heritage and Agri-Biodiversity.” I was invited to speak about “The Contribution of Young Boys and Girls in Documenting Odisha’s Agricultural Heritage.”

I felt anxious. The entire session was only one hour and fifteen minutes—I had just five minutes. How could I possibly convey twenty years of work and the efforts of hundreds of students I had worked with continuously since COVID in 2020? Finally, I decided to let the students’ own writings speak for themselves.

I shared the following examples:

On disappearing foods and migration: Rajani Khemund and Nalini Hantal, two girls from Godihanjar village in Koraput district, wrote that many traditional foods—kangu rice, sua rice, kodu rice, pitaa greens, aamasi greens, umar greens, pitaa tuber, serenda tuber, targai tuber, and nangal tuber—have been completely forgotten. Nearly 40 percent of the young people from their village have migrated elsewhere for work. This pattern appeared across data from nearly ten villages in the Koraput district.

On seed preservation: Students recorded how ridge gourd and bottle gourd seeds used to be hung from kitchen roofs for long-term storage. Students from Paikmal block learned traditional preservation techniques—coating cucumber and patalghanta seeds with pond mud and cow dung, then sticking them on kitchen walls. From her grandfather Madhab Sahu, Lopamudra Pradhan of Kudoguda village learned ancient skills: how people predicted rain by listening to insect sounds, how farmers read clouds to forecast harvests, how they judged soil fertility simply by examining pond clay.

On farming culture: Students wrote about how girls, daughters-in-law, and mothers once went in groups to transplant paddy. Even today, mothers work in the fields, but fewer girls join them. Earlier, entire villages helped each other, working in one another’s paddy fields in turn. Even girls from wealthy households would join others for transplanting. Professor Jayashree Sahu witnessed this in her own childhood.

On biodiversity: Regarding the Gandhamardan hills, Himani Pradhan of Baidapali village wrote that many traditional healers (vaidyas) lived there—hence the name Baidapali. One woman healer from her village has cured thousands of tuberculosis patients using the herb Cheramuli from Gandhamardan. Gayatri Danasana of Mandiaadhipa village in Paikmal block documented that Odisha has over 3,000 species of vascular plants, 130 species of orchids, and 12 species of ferns—more than half found in Gandhamardan alone. She compiled a list of over fifty medicinal plants from the region.

Recognition and Broader Impact

After listening to these accounts, everyone present was deeply inspired. Padma Shri Sabarmatee and Maya Nair, who chaired the session for the FAO, along with Nimisha Mittal, GESI Expert and Project Manager at FAO India, all emphasized how essential it is to expand such efforts.

They stressed that this initiative not only documents knowledge but also prepares the next generation to preserve the heritage and identity of their villages. Everyone acknowledged how timely and necessary this work is for recording and safeguarding our culture and heritage, not just for Odisha, but as a model for communities worldwide facing similar challenges of cultural erosion and knowledge loss.

Gratitude

It brings me joy to remember those who first conceptualized this work and helped us understand its importance. Sudhir Pattnaik, editor of Samadrushti, envisioned this initiative in 1994 and conducted the first experiments near Bhanjanagar with his friend Amulya Das. Professor Swadhinaranda Pattnaik and Professor Birendra Nayak inspired the work and helped it gain government acceptance in Odisha. Noted organic farmer Natabar Sarangi guided us during the documentation of village farming practices. Their vision continues to guide us, and we remain forever indebted to them.

We are deeply grateful to the Odisha Shree Anna Abhiyan and WASSAN for amplifying these youth voices and bringing this work to the national and international stage. A special thanks to Dinesh Balam, whose continuous guidance helped us give this work its rightful place and bring it to international recognition. His vision and support were instrumental in elevating village documentation from a local initiative to a global movement. We also thank the joy∞untu team for their partnership in taking this model across borders, demonstrating that participatory approaches to heritage preservation can thrive in diverse contexts.

We remain obliged to every individual, from those who conceptualized this work to those who continue to expand its reach, for their unwavering commitment to amplifying community voices.

Conclusion:

From one child’s observation about “darkness beneath a lamp” to a global movement illuminating community wisdom, this journey reminds us that the most profound insights often come from those closest to the ground. When we trust young people to document their worlds, they don’t just preserve the past; they light the way forward. Sohna Parveen’s words from 2003 continue to resonate today, reminding us that true development must reach everyone, especially those living in the shadows of progress. Through the pens of hundreds of children across Odisha and now beyond, we are not just recording history-we are ensuring that the voices of the marginalized are heard, their knowledge is valued, and their communities shape their own futures.