Connection with the Veenas

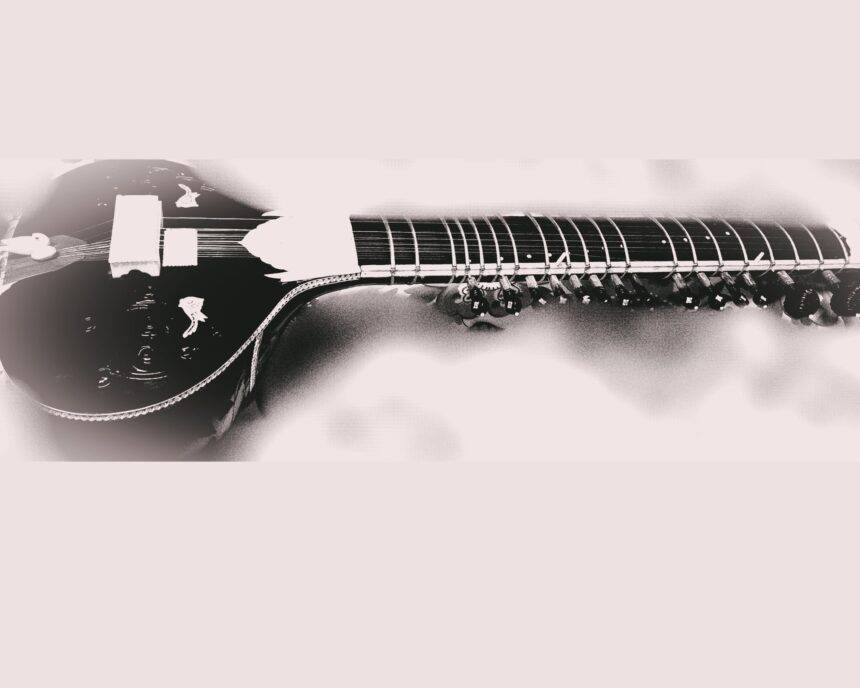

The first exposure to vidya (Knowledge) for a kid born into a traditional Hindu family in India occurs in front of an image or idol of Lord Saraswati, that is depicted playing an instrument somewhat like a veena. I say “somewhat like” since each image or idol has a unique portrayal. The ancient Vedic texts make mention of thousands of veenas. In a technical sense, the lute’s construction is a veena. Therefore, for the sitar, the most persuasive explanation for the Indians is that it evolved from some of these veenas, even though there may be other ideas about the sitar’s existence and genesis in India.

The chitra veena and tri-tantri veena are a few of the hundreds of veenas that are thought to have resembled the modern sitar. In his book “My Music, My Life,” Pandit Ravi Shankar mentioned these three veenas (Shankar, 2007). These veenas are said to have given rise to the current sitar. Nevertheless, relating the current sitar to these instruments appears to be more of an assumption than anything else. There must be a significant historical gap to verify these claims and identify the instrument’s true place of origin. The hypothesis appears to be little more than a supposition when each instrument is considered separately, together with the Vedic references (Bhatnagar, 2014).

Most likely, the misconception was caused by the phrase “She-tar,” which means “three strings,” and connects it to the tri-tantri veena. Furthermore, the seven-stringed chitra veena has a connection to the modern sitar. Nevertheless, the truth remains that there needs to be more evidence to support the existence of the sitar in its current form. Based on the number of strings, all of the veenas described are considered the sitar’s ancestors, whereas frets and other elements are disregarded. However, the frets are mentioned in relation to the numerous veenas described in the Vedas. Possibly denying the foreign Persian credits and tying the instrument to Indian traditions deals with such views (Mukherjee, 1976).

Amir Khusru and Sitar

“Apni Chhabi Chhabi banake jo men Pike paas Ayi

Jab Chhabi dekhi Pihu ki , to apni bhul gayi

Chhap tilak sab chhini re mose nena milaike

Baat adham kan dinhi re mose naina milaike”

For those who value art and literature, the great poet, philosopher, musician, and Sufi saint Amir Khusrow does not require an introduction. Amir Khursrow and many of his words will always be brought up in any literature discussion. Khusrau, known as the “Parrot of India,” served as court poet to several kings, Sultan ‘Ala-ud-din Khilji among them being the most significant Though Khusrau’s fame outside India is based mainly on his Persian poetry, in India, he is also remembered for his many putative contributions to Indian music. A Sufi, a poet, and a saint, Amir Khusraw learned Indian music and became a musician in a class.

The Sufi saint Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya served as Amir Khusrow’s spiritual guide. He was a passionate fan of devotional music. That is why Sufism was a significant influence on most of his poems. His spiritual and Sufi poetry conveys enduring love. Many of Khusrow’s poems are still utilized today as ghazals and bandishes in Hindustani classical music. He was known as “Khusru-e- shayra,” or the poet king, by Allauddin Khilji. He was both a court musician as well as an acclaimed singer. He was an expert in Indian music and well-versed in Persian music. He made an effort to combine the two genres. He is credited with initiating the process of blending Turko-Persian music with Indian music and with introducing numerous singing styles, new raga, taals, and musical instruments. Combining Persian, Arabic, Turkic, and Indian singing traditions, Khusrau also created new Ragas like Yaman and Zeelaf, Talas like Chakka and Soolfakhta, and musical genres like the Khayal, Tarana, and Qawwali.

Notwithstanding the fact that he made a significant contribution to Indian classical music, his place in Indian music history has been exaggerated. Numerous academic publications have made assumptions about Amir Khusrow’s function. It seems extremely overrated for one person to be credited for inventing so many genres, instruments, rag, taal, etc. Though Khusrau’s fame outside India is largely based on his Persian poetry, in India, he is also remembered for his many putative contributions to Indian music. Furthermore, no genre or musical instrument was created by a single person or generation. Only after it is passed down through generations does oral Indian music or genre become established.

It also makes no logic to attribute the invention of the sitar to Amir Hussain. Why is the instrument not mentioned in his writings if that were the case? The instrument is never described anywhere. Also, research casts doubt on the existence of a second individual named Khusrow Khan, who lived during Amir Khusrow and contributed to the instrument’s development (Vedabala, 2021).

Bio Data

Samidha Vedabala (Ph.D., Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata), a performer and researcher of Indian Classical Music, Sitar. She has been working as an assistant professor of music in the Department of Music at Sikkim University since 2011. Along with performance in music, she is actively involved in academic research in Indian music. She has published two books and many academic journals. Her book titled “ Sitar Music: The Dynamics of Structure and Its Playing Techniques” is one of them. Her professional and academic association with sitar inspires her to continue writing on the instrument and various aspects of it. Her work has been the source of information for one of the documentaries on sitar in the UK. She has also attended many national and international seminars on sitar music.

Samidha has been associated with Samadhwani for more than a decade as a writer.