Introduction:

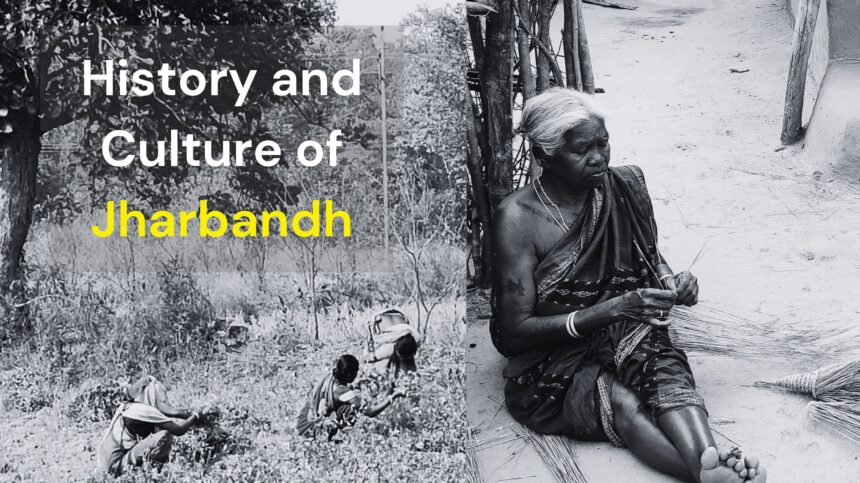

In 2023, when our Village History team visited Paikmal block to encourage schoolchildren to document the histories of their own villages, we had the opportunity to engage with Panchayat High School, Jharabandh. The students, teachers, staff, and especially the headmaster showed deep interest in the village history documentation work. They even requested us to organize a village-level meeting in Jharabandh, where community voices could be brought together.

One of the key concerns raised was the rapid change in local food culture. Once, this region thrived on millets such as mandia, kodo, and gunji. Today, however, millet-based diets have almost vanished, and most families cultivate cotton instead of traditional crops. Even though the majority of people here belong to Adivasi communities, their eating habits and agricultural practices have changed so much that village children often remain silent when asked if they have ever tasted traditional foods like mandia pakhala or gunji. This makes it all the more urgent to document the past foodways, agrarian traditions, and ecological memory of the region. Amidst this context, a Class 9 student of the school, Sanjulata Chhatria, came forward with her carefully gathered notes about Jharabandh. In our workshop, she presented stories of how her village was once filled with green fields, millet-based diets, indigenous farming, and community practices. Her hope is to see her village once again alive with greenery and enriched by the food traditions of the past. As a Student Historian of Jharabandh, Sanjulata’s sincere effort reflects both curiosity and commitment. By listening to elders, collecting forgotten memories, and linking them with her own vision, she represents the new generation that will carry forward the work of village biography. For her initiative and enthusiasm, she deserves our special thanks. – Editorial notes (Swayamprava Parhi)

Name – Sanjulata Chhatria

Village – Jharabandh

School – Panchayat High School, Jharabandh

Class – 9

History of Jarband:

The name of our village is Jharabandh. It is located about 45 km away from the Paikmal block headquarters of Bargarh district. From Jamseth Square, Jharabandh Panchayat is around 15–20 km away.

In our village, near the forest houses, there is a big pond. Since there were many bushes (latabuta) around that pond, our village came to be called Jharabandh. Earlier, the roads in our village were full of thorny bushes, and during the rainy season, they became very muddy. At that time, all the houses were mud houses, with tiled or thatched roofs. In the past, people raised many goats, sheep, cows, oxen, and buffaloes. There was only one tube well in such a big village. So everyone dug their own wells behind their houses. With that well water, they grew cabbage, pumpkin, radish, potato, coriander, mustard, chili, onion, brinjal, ridge gourd, and lady’s finger. There were no shops in our village. People went to Pethiapali market for their needs. Children wore dhotis, and young women wore simple cloth wraps. Clothes were washed using ash from burnt twigs. For bathing, people used to rub mud paste on their body and head. At that time, there were no matchsticks. People made fire by rubbing dry bamboo. Nobody wore slippers. There was no electricity. People lit up the house using dry firewood from the forest. There were no vehicles. People walked from village to village, or went by bullock cart. In the rainy season, mushrooms grew in plenty. Umbrellas were made from bamboo frames covered with siali leaves. Food was cooked in earthen pots. There was no school. Children studied under sheds called dera. Drinking water came from wells. Water was stored in clay pots (mathia). There was no television. On the radio, people listened to songs and the news. In those days, there were many trees. But when people started building houses and doors, they cut down many of them.

Food Practices:

In the past, the foods of our village included gunji, kodo, mandia (ragi), sargu (jowar), maize, and bajra. People also cultivated local varieties of paddy. Grains like gunji, kodo, sargu, maize, bajra, and desi dhan were pounded in the dhenki (wooden husking tool) and cooked into pakhala (rice gruel) to eat. Mandia was made into cakes wrapped in leaves, and also ground on a stone grinder to prepare mandia pakhala. Maize was roasted in earthen pots and eaten as makalia (parched corn). People boiled jaggery water and drank it like tea. They also ate mahua flowers after boiling them, and boiled tol chhali (a kind of forest root). Other foods included sargu puffed rice, jumer (a local leafy green), pipal fruit, and the tender stalks of kaiphul (a local flower). For curries (dal), they used many varieties: sirel leaves, muti leaves, bhadur leaves, feng flower leaves, limi flower leaves, sajana (drumstick) leaves, makhan leaves, karela leaves, kukodo leaves, bahal leaves, bhaji leaves, radish leaves, and cabbage leaves. From the forest, people ate the tender stalks of pita, kuliha, phalsa, and fruits like khudu. They also ate various wild roots like dhaikantha and kandamula.

I will tell you a story from our village:

Long ago, in our village, there lived two brothers named Duni and Kuhungi. The two of them used to sow chickpeas near the bund. The crop grew very well. But those chickpeas were being eaten at night by the king’s elephant from Patnagarh. When the brothers saw the footprints of the elephant, they thought: “It must be someone from our village, taking our chickpeas at night with their wooden shoes (chaki).” They told the chowkidar to gather the whole village and asked, “Whose shoes are eating our chickpeas at night?” So everyone tied their shoes with ropes and kept them at home. But still, the next night, the chickpeas were eaten again. The two brothers checked every house in the village and saw that all the shoes were tied. Then they thought: “If the shoes are tied, then who is eating our chickpeas at night?

So the next night, the two brothers kept watch over their field. And then they saw — it was indeed the elephant eating the chickpeas. The brothers took their bows and arrows and shot at the elephant, piercing its belly. The wounded elephant went back to Patnagarh, and the two brothers followed it. Right at the gate of the king’s palace, the elephant collapsed, bleeding and dying. The king saw this and ordered the brothers, “Pull out the arrow!” When the brothers pulled out the arrow, the elephant died instantly. The king was astonished. He realized that these two brothers had indeed killed his mighty elephant. But instead of punishing them, he was grateful. The king said: You two brothers have slain my big elephant. For this, I will reward you. And from now on, you two brothers will be the kings of Kumkhen From then onwards, the land of Kumkhen was given by the king, and the two brothers went and lived there.”